Florence is an iconic city known around the world as many people flock to visit her each year. It is the capital of Tuscany, which is one of 20 regions that form the country of Italy.

It is a city where its history is etched in its art and woven into its architecture. The city became the leading light in a new Europe after the darkness of the Black Death had pervaded it. This led to the birth of Humanism, which ultimately affected the birth of the Renaissance in the 14th -16th centuries. Much of this is down to the Medici family that saw an opportunity to build a dynasty. Each generation of the family were patrons of the arts and endowed much wealth into improvements to the city’s architecture.

The great beauty of Florence has left many a person in awe. Sore necks or even Florence Syndrome can be caused by the constant viewing!! Read on as I try to piece together Florence’s fascinating history, the characters that shaped the city and explain where the evidence for all this can be seen. This final blog on Florence (there are references to previous posts) is by way of summary of its history.

Florence Early beginnings

Originally founded by the Etruscans in the 6th & 7th centuries BC, it was supressed by Rome in 395 BC. Florence’s location was important as it was the only practical crossing of the River Arno as discovered in the post on Ponte Vecchio. The Romans saw the importance of the strategic location and as roads were built out of Rome, they knew that this location would provide access to Bologna and Faeza.

A military outpost was set up. This led to building of Roman structures like a theatre, spas, forum, etc. Sadly, there is little evidence of the Roman presence in the city although a visit to Vecchio Palace will allow you to see some Roman ruins (not accessible on my visit). The Romans named the city ‘Fiorentina’ meaning “flowering” (also the name of the city’s football team).

Florence in the Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages the city began to rise in prominence. It’s gold ‘Florin’ became the leading currency in the western world as Florentine banks established branches throughout Europe. This led to a war between Florence and Siena for control of Tuscany and the ultimate client the Holy See.

During 12th and 13th centuries the city struggled internally as factions who supported the Pope (Guelphs) clashed with those who supported the Holy Roman Emperor ((Ghibellines) – not to be confused with Rome – the emperor controlled most of central Europe before its defeat to Napolean and dissolution in 1806). The established banks in this period suffered an economic crisis in the 14th century as loans made to European sovereigns were defaulted because of the 100 years wars leading to their collapse.

It was during these struggles that Dante Alighieri was exiled and wrote ‘The Divine Comedy’. Born in Florence, Dante still looms large over the city. His body isn’t buried in the city. A read of his books and a visit to his childhood home (sadly hasn’t been completed) would provide ample information on the man himself. Sadly, all I learnt about him was from the large statue in front of Santa Croce, his cenotaph inside, and his Death Mask house in the Palazzo Vecchio.

Arnolfo also started works on 3 iconic buildings within the city, Basilica of Santa Croce, Palazzo Vecchio and Cathedral of Santa Marie del Fiore. At the same time city walls were constructed to protect the people.

Cosimo de’ Medici (Father of His Country)

In the 15th century the Medici family saw their opportunity and began forging their dynasty. As the Medici family was not of the aristocracy, it had to force their way onto to the scene. Their opportunity came after the banking collapse in the 14th century as Cosimo secured the papal account to add to his expanding network of banks.

As their wealth grew, Cosimo built important alliances and patronages. He used these to control and rule Florence. His main passion was building. Evidence of this can be gathered all around the city of Florence. Brunelleschi’s dome, the basilica of San Lorenzo, the convent of San Marco, Palazzo Medici Riccardi, the Medici chapel in the Basilica of Santa Croce and a chapel at San Miniato were all beneficiaries of Cosimo’s generosity.

Cosimo surrounded himself with the geniuses of the time. Many of the artists and sculptors were assured of commissions but were treated like friends. Cosimo organised an extensive and methodical search for ancient manuscripts. These were brought and stored in his library. Cosimo opened his library and held meetings with great people of powerful minds as they discussed these manuscripts and ideas. This led to the birth of Humanism.

Lorenzo de’ Medici (the magnificent)

Lorenzo de’ Medici was grandson of Cosimo and son of Piero de’ Medici. He followed in his grandfathers’ footsteps. He was also a patron of the arts and letters, a talented poet, a skilled diplomat, and a great ruler. His diplomatic skills brought peace and stability across the Italian city states.

He married into Roman nobility when he married Clarice Orsini. As the banks’ funds were draining up due to poor decisions and lavish spending, he planned for a future by getting his offspring a foothold in the church. Most notable was his son, Giovanni, who would later become Pope Leo X. He survived the Pazzi conspiracy of 1478 when the Pazzi family tried to rule, but his brother Giuliano was murdered in the plot. Giuliano had an illegitimate son, who would later become Pope Clement VII.

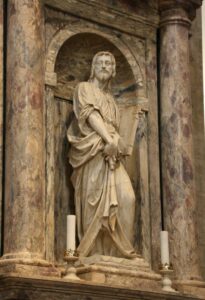

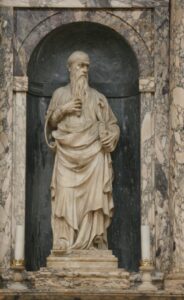

Lorenzo’s love of art was confirmed in his court of artists. It was filled with the great names of the 15th century renaissance. These included Piero, Michelangelo, Pollaiuolo, Verrocchio, da Vinchi, Botticelli, Ghirlandaio and Buonarroti. Evidence of their works are seen all over the city, most notably in the Uffizi Galleries, Galleria dell’ Accademia of Florence and The Bargello Museum.

A gap in Medici Rule of Florence

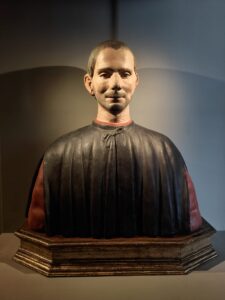

After Lorenzo’s death in 1492, his son (Piero) would take control of the city. He is often referred to ‘the Unfortunate’ which is unfortunate in itself!! He was ultimately banished from the city after a failure in leadership. This led to a gap in the Medici rule as Niccolo Machiavelli (bust is seen in Palazzo Vecchio and grave in Santa Croce) was appointed senior official in the Republic. Artists would come in search of fame and fortune.

A man called Savonarola, an ascetic Dominican friar, led an uprising amongst the people and effectually created a republic. Savonarola held extreme views and spoke out against the corruption of the clergy and excesses of the Renaissance. This was mainly accomplished from his base in the convent in San Marco (a place yet to be visited in the city).

He encouraged bonfires to be lit to destroy luxuries. The biggest of these took place on 7th February 1497 known as the bonfire of Vanities. Shortly after this the then current Pope, Alexander V, had him excommunicated. He was tried on charges of sedition and heresy. He was executed in Piazza della Signoria in 1498. He was only 46.

After Savonarola’s execution, Piero Soderini was declared Gonfaloniere of justice for life. I discovered his name in the room of 500 where he had instructed the two famous artists to paint scenes of Florentine history. He fled Florence after the Medici conquest of 1512.

During this time Lorenze’s son Giovanni was a cardinal to Pope Julius II. He used his close connections with the Pope to influence the addition of members of his family into positions of power. This was laid the groundwork for the future generations of the family. In 1513 Giovanni was elected Pope Leo X.

As head of Christendom, Leo X paid little attention to the church!! Strange, but true. Like his father he was more interested in the arts and letters. He drained the Vatican of its funds to support his extravagant patronage of the arts. He was so distracted by his patronage that he failed to pay sufficient attention to an unimportant monk by the name of Martin Luther but that’s another story. There are rooms dedicated to Leo X in Palazzo Vecchio.

Cosimo I de’ Medici (1st Grand duke of Tuscany)

Eventually the first grand duke of Tuscany, Cosimo, firmly restored the power of Medici rule in Florence. There is bold statue of him is the Piazza della Signoria. He became Duke of Florence at the age of 17 after his cousin Alessandro de’ Medici was assassinated. Cosimo was a strong and ambitious leader.

Cosimo reached out to Charles V (Holy Roman Emperor), who in exchange for Cosimo’s help against the French during the Italian wars, gave him the position of head of the Florentine state in 1537. He was elevated to the rank of Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1569 by Pope Pius V. Thus began the Medici hereditary rule that lasted until 1737.

Evidence of his rule is displayed all over the city as shown in previous posts. The decorations in the Palazzo Vecchio, the building of the Uffizi Gallery, Vasari Corridor and the purchase of the Palazzo Pitti.

Cosimo was a military man as well. Further exploration of Tuscany may provide evidence of his battles and what was built in Tuscany to secure the region. In Palazzo Vecchio in the hall of 500 the painting ‘Battle of Marciano’ is one of the 6 battle scenes that adorn the walls. This shows his successful battle over the city of Siena in 1555.

Cosimo married a Spainard, Eleanor of Toledo. Previous posts provide information about their time in the Palazzo Vecchio before they purchased the Palazzo Pitti.

Cosimo’s architect was a certain Giorgio Vasari. Cosimo commissioned Vasari for many projects and pieces of art. Evidence is all around Florence of their work. Frescoes inside the Brunelleschi Dome, the ceiling in the room of 500, remodelling and expansion of Palazzo Pitti are few that I have seen on my meanderings around the city.

Further Medici rule in Florence

Medici rule continued until 1737 when Gian-Gastone passed away childless. He was the 7th and final grand duke of the Medici family. Staring in the 16th century the dates are – Francesco I (1574-1587), Ferdinando I (1587-1609), Cosimo II (1609-1621), Ferdinando II (1621-1670), Cosimo III (1670-1723) & Gian Gastone (1723-1737).

Each generation of the family continued the family’s legacy. Lovers of arts and science they commissioned major pieces of artwork. These were done to show the association between the family, religion and political control. A more detailed visit to the Palatine Gallery in Palazzo Pitti and Uffizi Gallery would show the artworks commissioned and collected.

A visit to the Medici Palace and other museums around the city would show more of the vast collection of art gathered.

During these years patronage was given to astronomer Galileo Galilei whose grave was seen in the Basilica of Santa Croce.

By the time the Medici rule came to an end the duchy was bankrupt.

Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici, (1667-1743) who was the last in the family dynasty donated the Medici collections to the city of Florence. That was some gift.

Florence after Medici rule

After the rule of the Medici family, Florence was governed by the Habsburg-Lorraine dynasty. It was briefly interrupted by Napolean but their time came to an end in 1859. Florence then annexed itself to the new Kingdom of Italy. It was around this time that the facades of Santa Croce and Cathedral of Santa Marie del Fiore were completed. As the new Kingdom of Italy was being formed Florence served as its capital between 1865-1870. Sadly, during these years much of the city was altered. City walls were pulled down as urban expansion took place (walls remain around the edges of Boboli gardens).

German occupation during the later stages of World War II resulted in Ponte Vecchio being saved, mercifully, as all the other bridges were blown up to halt the allied advance.

I have discovered in previous posts how the river caused death and destruction in 1966. A total of over 100 people were killed along with huge amounts of damage to the city’s art. “Angels of Mud” (Angeli del fango) was the name given to the people who came from all over the world to try and save as much of the art as possible.

Florence Conclusions

Florence now is now a popular and a ‘must see’ tourist hotspot. A constant hub of activity as people arrive at the Tuscan capital. Maybe Anna’ de’ Medici didn’t foresee the vast appeal the city and her family’s art collection would have but we’re grateful to her act of kindness in leaving it to the city.

A visit to Florence can be incredible and frustrating at the same time. Is there such a thing as too many tourists? A visit to Michelangelo square at sunset or walking across Ponte Vecchio or general walking the streets will provide the reason for frustration. One wonders if such have discovered anything of the tremendous history of Florence, taken an open mind to artistic endeavours and enjoyed an open-air classroom.

I came to Florence for differing reasons; my knowledge on the city was sadly limited to a TV show. I soon began to realise than I needed to delve into the detail and return to explore this majestic city. Many books have been purchased and read to aid this thirst for knowledge. The result of this has been surprising.

My interest in and admiration of the arts has developed beyond recognition and perhaps set the pathway to future posts. My desire to learn has only been encouraged by my visits to Florence. The fire within burns ever brighter as further tours and visits of the surrounding area and rest of the country are planned. As I’m starting to find out, Tuscany is more than just Florence.