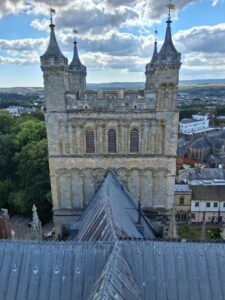

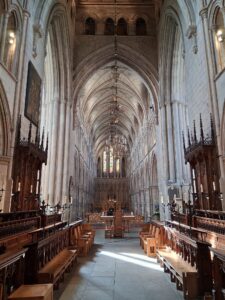

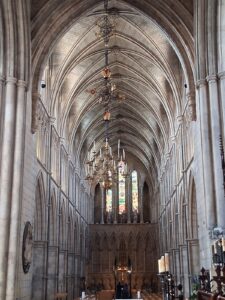

Sainte-Chapelle is a medieval masterpiece, a jewel of high gothic architecture and the epitome of master craftsmanship. King Louis IX’s royal chapel is nestled on the small island of Ile de la Cité, the birthplace of the city.

Various signs point wanderers to its existence, but these are often ignored as people seek the more illustrious monuments in Paris. A prime example, and a short walk away, the towering Notre-Dame draws a crowd. And rightly so! This, however, shouldn’t be to the detriment of a visit to Sainte-Chapelle. How many people ignore the splendour of this chapel in pursuit of the Parisian tick box exercise.

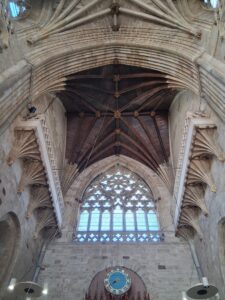

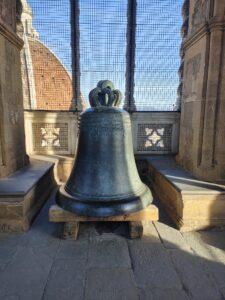

The majesty and splendour on display are truly sights to behold. This is remarkable when it is considered that this building was built in under 7 years – a record time in the 13th century. A palpable silence graces the scene of the upper chamber as you stand in amazement at the creation before you. It was built to house the prestigious relic of the Passion of Christ: the Crown of Thorns. King Louis IX paid a remarkable sum to buy this but another eye watering figure to store it.

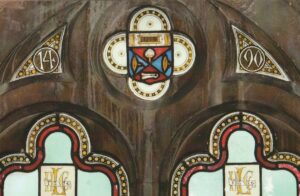

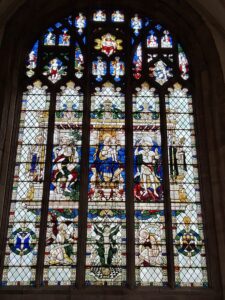

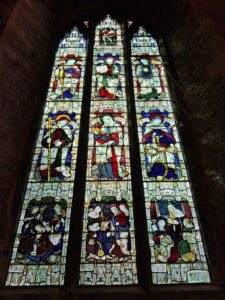

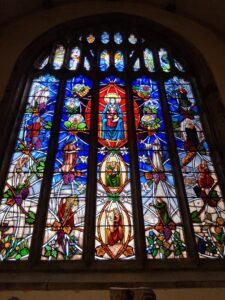

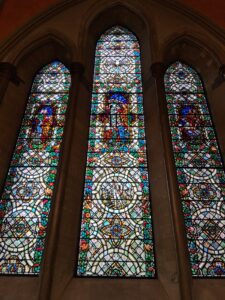

This tiny jewel is like no other. The walls are filled with deep and colourful stained-glass which create a royal display around you. Surrounded by breath-taking detail you feel lost in the tunnels of time. Each arch of the window feels like a new chapter in a book with the individual piece of glass creating a medieval storyboard. This kaleidoscope of glass is mesmerising as you stand in admiration.

Join me as I learn about the man behind the chapel and why it was built.

Who was King Louis IX?

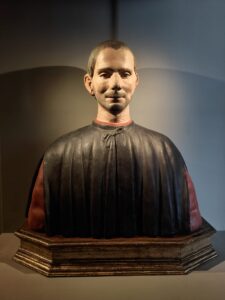

This is an important place to start. I discovered his name when exploring Hotel des Invalides. Louis IX was a devout Catholic monarch known for his piety, justice and leadership of two crusades.

Born on the 25th of April 1214 his parents were Louis VIII King of France and Blanche of Castile. Louis inherited the crown from his father when he passed away (d1226). He was crowned in Reims at the tender age of 12. Blanche acted as regent until he came of age, and then he ruled France until his death at the age of 56 in 1270. Henry III was king of England at this time. Remember much was discovered about his government rulers in Wales.

The Ile de la Cité is one of two natural islands in the river Siene. Louis was part of the Capetian dynasty that developed much of the island before the monarchy moved onto the Louvre and Bastille.

King Louis & the seventh crusade

In 1248 King Louis IX led the seventh crusade (1248-1254) to recapture the Holy Land by first conquering Egypt. This campaign was to end in defeat. Captured and ransom demanded, it was paid, but rather than return home he stayed in Acre in northwestern Israel. Here he was able to use diplomacy to bring some success after his defeat.

When his mother died, he returned to France. Years passed as he managed the country but there was a desire burning within to return to the holy lands. In 1269 he decided to go to Africa and stop the Muslim advance. This was a fatal decision which resulted in him dying in Tunis.

His body was returned to France, a long journey through Italy, over the Alps through Lyon and onto Paris. His funeral took place in the Notre-Dame before his coffin was sent to the tomb of kings at the abbey of Saint-Denis (a place not visited but must be if I return to Paris).

In 1297 Pope Boniface VIII canonized Louis IX. Louis IX became the only King of France to be a saint in the Roman Catholic church.

Acquiring relics

Louis IX purchased the crown of thorns from a financially troubled Beaudouin II of Courtenay (Latin emperor of Byzantium) after a two-year negotiation in 1238. Louis IX added a piece of the cross and a nail to the collection of relics.

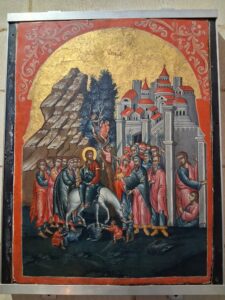

The relics were to be housed in the Notre-Dame. King Louis IX was presented with the relics a few days prior to a grand procession through the city to Notre-Dame on 19th of August 1239. In this procession Louis IX abandoned royal attire, wore a simple tunic, carried the crown barefoot through Paris.

Commissioning Sainte-Chapelle

After the relics had arrived in Paris, Louis IX decided that he needed somewhere to keep them safe. Louis IX commissioned the construction of a royal chapel in the medieval Palais de la Cité. As previously mentioned, this was the former residence of the Kings of France until the 14th century – it is now the court of justice. Who the architect was is unknown as is the start date of building. What we do know is that Sainte-Chapelle was consecrated on 26th of April 1248.

Sainte-Chapelle Design & Architecture

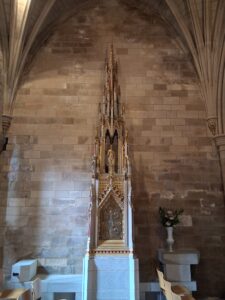

Its reliquary shape gives it a striking vertical appearance. It is made up of an upper and lower floor. The lower floor is robust and powerful and provides the foundations to the upper floor. Palace staff would have used the lower floor, which today is now where you enter and have a look at information boards and displays.

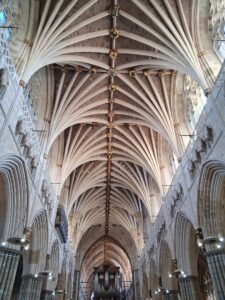

You then take a narrow spiralling staircase into the upper level where the king entertained distinguished guests. Splendour radiates all around you as the light pours through the glass. The upper chapel consists of 4 bays which ends in a seven-sided chevet. This wraps around the Chasse and where the relics would have been housed in a casket.

In between the pillars, which are strengthened on the outside by buttresses, is a collection of stained glass, two in each bay on either side totalling 8 and then 7 around the apse at about 15m high.

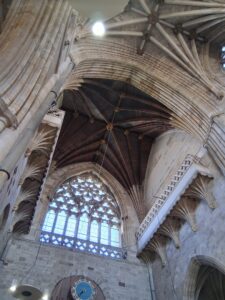

Let there be light. The colourful glass display portrays 1113 scenes from the Old and New Testament. An additional rose window was added in the 15th century. The ceiling is fan vaulted and seems timid in comparison to the beauty of its walls.

Surviving the Revolution

After surviving fires and flood in the 16th and 17th centuries came its most important fight. As a symbol of religion and royalty Sainte-Chapelle was at huge risk. Thank goodness that it did survive although not without some damages and vandalism.

The relics were dispersed although some survive and were moved into Notre-Dame. Here they have remained and miraculously they survived the fire that destroyed Notre-Dame in 2019. The grand Chasse itself was melted down long ago during the French revolution.

External sculptures and royal emblems were smashed at the same time Along with pulling down of the spire (a new one was to be built in 1853-1855). Internally some of the glass was broken and taken out. This resulted in about two thirds of the original glass remaining.

The building was used as a grain store before being turned into civil use as the archives of the Palace of Justice. In 1840 under the reign of King Louis-Phillipe I a restoration of the chapel began. It was during the revolution that it lost its church status (like the pantheon) and became another monument of Paris.

Is Sainte-Chapelle the best of all Parisian monuments?

It is hard to find any argument for it not being the best. It is, without doubt, beautiful. The incredible engineering feats achieved all those years ago puts modern achievements in the shade. It truly is a masterful piece of artwork.

It has history – tick. Dating to the 13th century is has hundreds of years of history. Meaning that it has stood the test of time.

It survived the revolution – tick. It somehow managed to survive though as a symbol of the church and monarchy it didn’t have much hope of doing so. But survive it did, thank goodness.

Beauty – tick. The stained glass on display creations a colourful display that will leave you breathless and speechless.

Peaceful – tick. It most definitely is accessible for an entrance fee. The crowds aren’t here. Why people ignore Sainte-Chapelle when visiting Paris is beyond me.

Are people really that blissfully unaware of its beauty and existence? Do religious buildings not appeal to the masses? Are people led to conform to what is cool or not cool by social media feeds? Is it hard to find? Possibly! But with all the technology at our fingertips there are no excuses. Perhaps they haven’t discovered Marks Meanderings and been inspired to visit.

Well, I hope that I have inspired you to visit this secretive and seductive reliquary. Stepping inside is a dazzling and awe – inspiring moment as the natural light radiates its way through the stained glass.

This is, in my eyes, Paris’s best monument. It’s nestling location in and around the palace of justice may hide it from view. The signs certainly point you in its direction, but it doesn’t stand out of the Parisian skyline like its neighbours – the famous Notre-Dame, the monumental Arc de Triomphe, the piercing Eiffel Tower and Sacré-Cœur which keeps a watch over the city.