A visit to Abergavenny Castle and museum is very pleasant and thoroughly enjoyable. It is a place marked by intrigue, deception and murder throughout its long history and is associated with Welsh Marchland castles and the English Civil War.

Abergavenny Castle sits above the River Usk, with panoramic views as far as the Blorenge, Sugarloaf and Skirrid mountains (all worth a climb). Sadly, all that remains of the castle is a small section of picturesque ruins. Imagination is required!! These ruins are hidden from sight when visiting the town but follow the signs to the entrance gates where notice of free entry assists any with an inquisitive mind.

Join me as I explore another Marchland castle. It shares a similar history to those that have been recently visited but with a couple of dramatic and treacherous events. From its very early beginnings, it was an important castle. It played host to visiting monarchs as well as being the headquarters of the lordship of Abergavenny.

Abergavenny Castle History

Abergavenny Castle was established in 1087 by the Norman’s first Lord of Abergavenny – Hamelin de Ballon. The initial castle was motte and bailey. The motte is still clearly visible. Hamelin de Ballon, along with his brother Wynebald de Ballon, founded the Benedictine Priory in the town (will explore that later).

Hamelin’s two sons died without leaving an heir, so the inheritance was passed to Hamelin’s nephew Brian Fitz Count. Brian, like his uncles, left no heir so the Abergavenny Castle reverted to the crown (Henry II who reigned from 1154-1189). This Lordship of Abergavenny was then passed to 1st Earl of Hereford – Miles FitzWalter of Gloucester.

The lordship passed through all his sons (one of the sons, Henry FitzMiles, was killed by forces of Seisyll ap Dyfnwal – many Welsh names of the time feature the word ‘ap’ meaning ‘son of’), but with none of the sons having any heirs, the inheritance passed to the daughter Bertha.

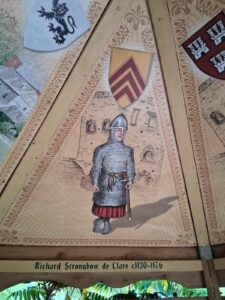

She was already married to William de Braose who became very powerful at the result the unexpected value in the marriage. His son, also called William (there were a lot of people called William de Braose who were lords at this time – this one was the 4th Lord of Bramber, in Sussex, and lord of a number of places including Abergavenny and even places in Ireland and France), would become the most famous family member.

Christmas Massacre 1175

During these times there was a lot of tension between the Welsh princes and Normal lords in Wales. It took a turn for the worse when Henry FitzMiles was killed in the 1160s by Welsh forces of Seisyll ap Dyfnwal. William de Braose took it upon himself to avenge Henry’s death.

William’s treachery and trickery played out at Christmas 1175. He organised a dinner and invited Welsh noblemen and, of course, Seisyll, and his eldest son, for dinner. His invitation was, nominally, to overcome their differences and find a new path to peace. Upon their arrival they were asked to surrender their weapons at the gates (why did they do that?), before entering the Great Hall.

Once inside the doors were bolted shut and instead of a peaceful dinner and negotiations, the armed men of De Braose slew all inside. Once the gruesome act was complete, William and his men rode to Seisyll’s house and, reputedly, murdered his youngest son (aged 7) and captured his wife. De Braose’s had his revenge for his uncle’s death.

Revenge 1182

The result of William’s ruthless revenge sent shock waves across the land. The massacre was not well received by the English monarchy (Henry II). The castle and lands were removed from William and passed to his son, also called William (there’s a surprise!!) who had committed the atrocious act. The Welsh sought revenge, which was achieved when Hywel ap iorweth (Lord of Caerleon) attacked Dingestow Castle (which was destroyed) and Abergavenny castle (which was burnt).

Abergavenny castle rebuilt, attacked and rebuilt

Abergavenny’s strategic location was still important, guarding the River Usk and surrounding lowland areas. The De Braose family was in favour with King Richard I (reigned 1189-199) and King John I (reigned 119-1216) so work began to rebuild the castle. A new keep, surrounding stone curtain walls, and towers were built in red sandstone. King John I visited the castle in 1215.

In 1233 Abergavenny was one of the many castles in the region attacked and destroyed by Earl of Pembroke.

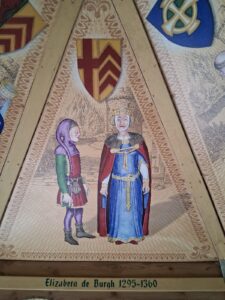

After the De Braose association with Abergavenny castle came to an end, it passed through the De Cantilupe family (they married into the De Braose family) to the Hastings family in 1273. The Hastings family continued an expansion program of the castle with two western towers, a circular and a polygonal tower added. The remains of these works are what may be seen today. Some members of the Hastings family, along with Eva De Braose, are buried in the Priory Church of St Mary.

Abergavenny Castle & Owain Glyndwr

The Owain Glyn Dwr rebellion swept across Wales early in the 15th century. As I learnt during my visit to Usk Castle, this threatened the security of the English in the region and an alarmed King Henry IV (reigned 1367- 1413). King Henry IV gave instructions to strengthen and reinforce Abergavenny castle and increase the size of the garrison.

The barbican (which you walk through first) was built to replace the original gatehouse. The then current lord was William Beauchamp. In 1404 the town of Abergavenny was besieged by Owain Glyn Dwr and his followers, but the castle was never captured or damaged. St Mary’s Priory didn’t fare as well; I shall explore this in more detail when I visit. William Beauchamp was ordered to stay at the castle and defend it and the town until 1409. The garrison included some 80 mounted soldiers and around 400 archers.

Civil war at Abergavenny Castle

In the years after the Owain rebellion Abergavenny’s castle, like the other castles visited in the region, began to fall into a state of ruin so that by the time of the Civil War (1642-1651) the castle required reinforcement.

Abergavenny castle at this time was held by the royalists, loyal to King Charles I (reigned 1625-1649), who was to visit the castle twice in 1645, trying to raise a new army after being defeated at the battle of Naseby. When King Charles I left the second time, the Roundheads (Parliamentarians but also called Roundheads by their enemies because many of them had short, cropped hair) were fast approaching, and he ordered that the castle’s living quarters be destroyed.

The back-and-forth nature of the Civil War meant that after Charles I had abandoned Abergavenny, the Roundheads made it their base a year later. The Parliamentarians were able to hold Abergavenny after the royalists attacked the castle. Two years later, in 1647, after the surrender of Raglan Castle (in 1646) had taken place, orders were given to slight the castle (make it indefensible).

19th century – Abergavenny Castle

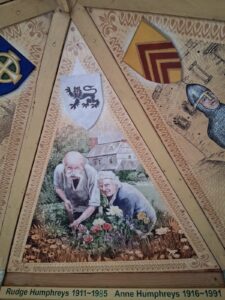

Sat on top of the motte (the oldest part of the castle) is a conspicuous building. It is the former hunting lodge (now the Abergavenny Museum) built by the Marquess of Abergavenny (William Nevill) in 1818-19. Though a relatively modern building, it was built to look like a former medieval keep. In 1881 the castle grounds were opened to the public due to the increasing popularity of the picturesque views that were possible.

Abergavenny Castle Today

Abergavenny Castle is sandwiched between the shops of this market town and the river Usk. Abergavenny Castle is a hidden gem and loaded with history.

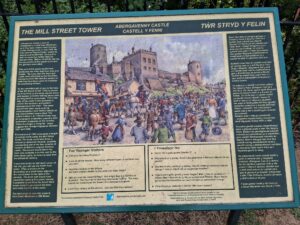

It is an atmospheric and historic spot for a picnic, to meet people and for kids to run about tirelessly. If kids can be persuaded to take a break from expending their energy there is much for them to learn. Some research and reading are required to understand its turbulent past but carefully situated around the ruins are numerous information boards. These provide detail on what the castle would have looked like.

A walk up the former motte is highly recommended. “Why?”, I hear you ask. The views are rewarding and you’ll find Abergavenny Museum. The museum, like the castle and grounds is free to enter, and provides much information and resources about the town and castles history.

Abergavenny Castle has similar history to other nearby castles (Usk & Three castles) visited. Its fascinating history has brought different characters to the fore and opened other avenues to pursue. I hope you enjoy visiting as much as I have.