Introduction

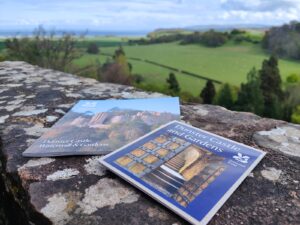

As I walk through Greenwich Park and up a steep hill, I begin an approach to the former site of Greenwich Castle. Once at the top it is easy to see why this would have been the perfect location for a castle. The views from the top are rather impressive. Sadly, the castle is long gone, and though I was not here primarily for the wonderful views over the Thames and greater London they were a bonus. I was here to visit the ‘Royal Observatory’, another London Landmark and part of the Royal Museums Greenwich. This was to be a meandering full of education, and one that, as always, I hope provides inspiration! During this visit I delved into the world of astronomy, time, longitude and latitude. Read on as I walk back through the corridors of time on a voyage of discovery.

Early beginnings

During the 17th century England had suffered some turbulent times. I have always been fascinated by the struggle between Oliver Cromwell and Charles I. I have never paid much attention to what happened next. After the Civil War, then the execution of the king in early 1649, the subsequent republic and then the death of Oliver Cromwell, the monarchy was restored. Charles II was defeated by Cromwell at the Battle of Worcester in 1651 and had to flee to Europe where he remained in exile until 1660 when the English throne was restored to him. He was 30 years old. He was a controversial character but left a lasting impression by way of improvements in navigation and ship design.

Under his orders he founded the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. The world and, particularly, European nations, were now relying on the sea for trade as their empires were expanding. These ships needed to know where they were headed. Incredibly they could work out their position using the sun and stars to work out North and South (latitude). They had no idea how to work out East and West (longitude). So, Charles was convinced by leading scientists that an observatory was needed to find longitude and put England back at the forefront of seamanship.

Flamsteed House

John Flamsteed was appointed as Charles II’s astronomical observer. As he was the first Royal Astronomer, I begin to understand why the oldest building at the Royal Observatory is named after him – Flamsteed House. John was appointed on 4th March 1675, but it wasn’t till 22nd June that the decision was made to build ‘a small observatory within our park at Greenwich, upon the highest ground’.

The name Christopher Wren has come up in my previous meanderings in Oxford and more recently at Kensington Palace. A well-known architect, I have yet to write about his most famous work, St Paul’s Cathedral, London. Watch this space! Before Christopher became a well-known architect, he had been a professor of astronomy at Oxford. He and his assistant, Robert Hooke, suggested the ruined site of Greenwich Castle. They reasoned that solid foundations were already in place, there was excellent access to London via road and river, and the site was far enough away to avoid air pollution from the city.

The foundation stone was laid 10th August 1675 by John and 11 months later, on 10 July 1676, he moved in. John was to spend the next 40 years observing the moon and the stars. On entering Flamsteed House, you are provided with information regarding the 10 Astronomers Royal that lived and worked here:

John Flamsteed (1675-1719), Edmond Halley (1720-1742), James Bradley (1742-1762), Nathaniel Bliss (1762-1764), Nevil Maskelyne (1765-1811), John Pond (1811-1835), Sir George Biddell Airy (1835-1881), Sir William Henry Mahoney Christie (1881-1910), Sir Frank Watson Dyson (1910-1933), Sir Harold Spencer Jones (1933-1955) & Sir Richard van der Riet Woolley (1956-1971).

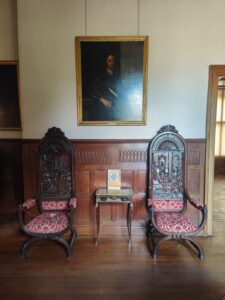

As I walk round Flamsteed House it becomes clear that the Royal Observatory’s life began to evolve from the early days of a basic observation post into more of a family home. The tour looks at the families of two of the Astronomers Royal and their families – The Maskelyne & Airy Family. Observatory life began to change as guests would be wined and dined, and the families began to live with the astronomers. This meant that Flamsteed House was expanded to accommodate more people as seen when walking around.

The Octagon Room

As I leave the first rooms visited, we make our way up into the Octagon room. It is a bland and tall room, full of windows which beam natural light in and is filled with clocks. The eye is drawn to the many fascinating devices. When the room was built there were no instruments installed so John Flamsteed had to bring in all his own.

The Octagon room design didn’t consider the true north south line so, was unsuitable for measuring star positions. Instead, John used this room for the observation of specific events like the appearance of comets and eclipses. Most of his work was completed in a purpose-built structure nearby. A lot of the clocks in there were supplied by Thomas Tompion, London’s leading clock maker and paid for by John’s patron, Sir Jonas Moore.

The time ball at Royal Observatory

The rest of the visit to Flamsteed house is spent looking at a vast array of clocks, chronometers and other such devices. The Royal Observatory established itself as a centre for measuring and sharing time.

When leaving the house, look immediately at its roof. You will notice a funny looking pole, located on top of the Octagon Roof, with a large red ball. This was an installation by John Pond, the sixth Astronomer Royal, in 1833. Nearly 200 years later it is still in operation. Fortunately, I timed my visit to witness the time ball descend at 1300 though I had no prior knowledge that this event took place each day. This time ball is dropped to provide a visual time signal. Having walked up from the River Thames I reckon that a telescope is needed to observe the red ball and its movement.

It was designed so that all the ships at the docks in London could see the ball drop and know that it was 1pm and set their clocks to the right time. You could say that this was the beginning of establishing Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) as measured at the Meridian Line (the earth’s zero degree line of longitude). I found it interesting to learn that, around Britian up until the mid-19th century, the sun was used to set local time in villages, towns and cities. For example, this meant that Yarmouth to the east was 7 minutes ahead of Greenwich and somewhere as far west at Penzance was 22 minutes behind.

The development of railways was to change all this. There was the need for a centralized time. The chaos and lack of management from trying to run a timetable where every destination was in a different time zone on such a small island is beyond contemplation. Sir George Airy saw the potential in a new clock system. He ordered one for Greenwich which was made by Charles Shepherd of London and had it mounted on the gates to the Observatory. It is known as ‘The Shepherd Gate Clock’. It was then linked to other parts of the observatory and London train stations.

Airy wrote of this system ‘I cannot help but feel a satisfaction in thinking that the Royal Observatory is thus quietly contributing to the punctuality of business through a large portion of this busy country’.

The Meridian Observatory

The other important building of the Royal Observatory is the Meridian Observatory building. I mentioned above that John Flamsteed did most of his work away from the octagonal room in a purpose-built structure. By the time his successor took over the building was subsiding and falling away which meant that subsidence rates had to be factored in to measurements of star positions!! Edmund Halley commissioned a new building to replace the old and installed an improved quadrant device and accurate timekeeper supplied by the prestigious clock maker from London George Graham.

James Bradley was Halley’s successor, and he was granted money to build additional spaces to Halley’s original buildings, which included a new observatory, bedroom for the assistant, a library and calculating room. These were the rooms which I saw on my visit. It is also where the astronomical work was completed until the 1950s before such work was carried out at the rural location of Herstmonceux in East Sussex.

As time went on, each Royal Astronomer kept collecting more data and improving the instruments in use. The 7th Astronomer, George Biddell Airy, designed the Airy transit circle. This was the defining instrument of the world’s prime meridian. Unlike the equator which provides a natural zero line north and south there wasn’t a natural prime meridian for longitude.

In 1884 at the international Meridian Conference in Washington delegates recommended that the Meridan passing through Greenwich should be used. They also recommended that Greenwich be the starting point of the day, year and millennium at the stroke of midnight Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). This applied to the whole world thus creating the time zones system with which we are familiar today.

The Camera Obscura

Across the courtyard from the Prime Meridian line is the camera obscura. This is an example of how attempts were made to capture images before photography was invented and developed. This obscura was a former summerhouse. On clear days you can see a projection of Romney Road and the Queen’s house.

Sadly, this isn’t the original. John Flamsteed’s original was removed quickly after his tenure before Nevil Maskelyne installed a new one during his stint at the observatory. The one that I visited today was built in 1994 and provides a chance to see London the way they did back in the day.

Conclusions about Royal Observatory

This concludes a fascinating and educational visit to the Royal Observatory. Being close to the Cutty Sark it was convenient to expand my knowledge of Maritime Greenwich. The visit to the Royal Observatory taught me about longitude and latitude. I found out that it is possible to navigate using the moon and the stars! The importance and history of this site will be remembered every time I talk about time, travel, etc.

The visit has also challenged me to revisit Christopher Wren’s masterpiece and finally write about St Paul’s Cathedral. Yet, surprisingly, it has given me a completely different direction in which to travel as I feel a visit to Herstmonceux in East Sussex would prove very inquisitive and interesting in building on the knowledge gathered here. I hope that you have enjoyed reading about my visit to the Royal Observatory and have joined me in learning about longitude, latitude and GMT.