‘Three Castles’ refers to a trio of Norman castles set in the Monnow valley in southern Wales. The Monnow valley is carved into the hills of Monmouthshire and very close to the English and Welsh border. The castles of Grosmont, White & Skenfrith are excellent evidence of the turbulent history of the Welsh borderland area (known as the marchland or marches) in the medieval centuries.

After their conquest in 1066, the Normans set about protecting whilst expanding their newly acquired kingdom. The Three Castles are each of motte and bailey construction and were to protect the route between Wales and Hereford. Much of what we see today is due to Hubert de Burgh’s foresight.

Join me as I explore each of the ‘Three Castles’, cheating slightly as I drove to each one, rather than doing the 19-mile circular walking route between them. I learn about motte and bailey castles and explore some of the fascinating history of England and Wales. Each individual castle is surprisingly free to enter and now managed by either the National Trust or Cadw (a Welsh organisation protecting historic sites – cadw is a Welsh word meaning to keep or protect).

Motte & Bailey castles

This style of castle was basic in construction, relatively quick to build, and designed to intimidate. The Norman motte and bailey castles were built in strategic locations to help consolidate power and secure towns after their successful invasion.

Motte & bailey castles were made up of two structures – a motte, and a bailey. The word ‘motte’ means mound which was often artificial but sometimes on a natural formation. It was the chosen place to build a wooden or stone keep on its top. This was then surrounded by a palisade (a defensive wall of pointed wooden stakes). The height of the mound provided a valuable viewpoint out across the local landscape with the mound providing a line of defence against attackers.

At the bottom of the motte would be a protected area known as a bailey. Any palisade built was there to protect buildings as another layer of defence. In some cases, outside these fortifications there would have been a ditch or moat offering yet more defence. A gatehouse provided entrance/exit to and from the castle.

History of the Three Castles

Looking back through time doesn’t provide much evidence as to who first established the origins of the Three Castles. Possibly it was William FitzOsbern, Earl of Hereford, who instructed some basic fortifications at the sites of the Three Castles to be built towards the end of the 11th century.

But by the 12th century there is evidence of their existence. After a couple of rebellions, the most notable being in 1135, the then current King (Stephen) unified the three castles under one lordship known as the Three Castles.

The Three Castles in the 13th century

At the beginning of the 13th century a name that is symbolic with all three castles is that of Hubert de Burgh. Hubert was an excellent military man and a loyal servant to King John I who rewarded him with the lordship of the ‘Three Castles’.

Hubert would fall in and out of favour with the monarchy. In his pomp Hubert was one of the most influential and powerful men in England as he took on the role of Chief Justiciar and given the title of Earl of Kent.

The ownership of the Three Castles passed to his rivals a couple of times during his ownership when he fell from grace. Much of the Three Castles we see today is the result of the works undertaken by Hubert.

When Hubert passed away the castles found their way back to the monarchy. On the throne at the time was King Henry III. Henry III completed some works on the Three Castles before granting them to his eldest son, Edward (later Edward I) before they were passed to his second son Edmund ‘Crouchback’ Earl of Lancaster (second son of Henry III).

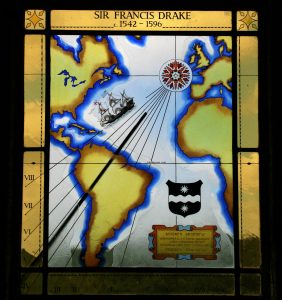

This was the start of a lengthy association between the Three Castles and the earldom (later duchy) of Lancaster. This ended in 1825 when the castles were sold off. Henry III’s son, Edward I was known as Edward Longshanks (Hammer of the Scots, William Wallace and all that). Before his wars in Scotland, Edward I conquered Wales in 1283 with the help of his brother. A result of their success made the Three Castles and other castles in the region redundant, as the whole of Wales fell under English rule.

Last military action at Three Castles

The castles maintained an administrative position and were maintained in the years after. The Three Castles saw their last military action in 1405. A year earlier in 1404 Owain Glyndwr lead a revolt to overthrow English occupancy in Wales. He besieged the castle at Grosmont in 1405, but a force sent by Prince Henry (later Henry V – born in nearby Monmouth) defeated them. This was a prelude to the Welsh attack on Usk castle (a place I will visit shortly) a few months later which ended in disaster.

As a result, by the 16th century, the Three Castles had fallen into a state of disuse, disrepair and ruin and never to be recovered to their former glory. Now the ‘Three Castles’ under the ownership of Cadw and National Trust provide us with an insight into their wonderful history.

White Castle

The first of the three castles visited is White Castle or to use its original name was Llantilio Castle. The castle is very remote and completely detached from civilisation. Its ruins are excellent evidence of the motte and bailey castle, although the signage and guidebook refer to the motte (inner ward) and bailey (outer ward).

It seems to be the furthest away from the English/Welsh border and the last of the three to developed. Its location may explain why it never saw any military action. Finding a safe space to park the car was tricky. A gentle stroll from the car park led me to the outer gatehouse.

White castle is now a peaceful ruin. It clearly shows the curtain wall that surrounded the outer ward. Evidence can be seen of 4 towers placed at different points of the wall along with the gatehouse. Entry is through the gatehouse. As you walk over a bridge the ditch that would have surrounded the outer ward is evident. The outer ward is now a wild meadow and perfect spot to have a picnic. It is hard to imagine the hustle and bustle that would have been here in medieval times.

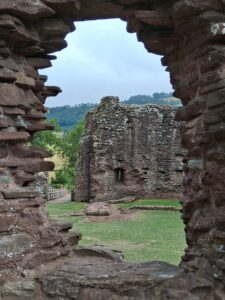

Leaving behind the outer ward I approach the bridge across the moat (severely dried up after a long hot summer). Two imposing round towers help form the inner gatehouse. Upon walking through and into the inner ward it is completely derelict. There is broken gap in the curtain walls in one corner, otherwise the walls remain intact although not accessible.

In the inner ward the floor plan resembles a pear shape, with ground evidence of a chapel, hall, kitchen, accommodation and a well. There were enough facilities to make the castle habitable for previous owners. Cross shaped windows provide some views of the neighbouring countryside.

Skenfrith Castle

The second of the Three Castles visited was Skenfrith Castle, which, unlike White castle, is in the centre of a small village. The river Monnow meanders alongside the edge of the castle and was used to provide the water for the moat. In the middle of the village there is a charming church (St Bridget’s) which is well worth exploring whilst on the outskirts is delightful restaurant and hotel (The Bell Hotel) which provides refreshments and accommodation.

This castle is also now owned by the National Trust and managed by Cadw. Perhaps it is this combination of owner and manager that has been instrumental in continued free entrance. Parking can be made right next to the castle and a short walk to the entrance is made before climbing some steps into the raised earthworks of the castle.

Skenfrith Castle could be literally described as 4 walls and a keep, a quadrilateral floor plan with towers in each corner. In the heart of the castle is the remains a keep tower. All the ruins that are witnessed here are from the Hubert de Burghtenure. Upon acquiring the Three Castles Lordship he pulled down the existing castle and rebuilt the current one. Apparently, it was easier to do this than modify what was already in place.

As you enter the inner ward, you’ll be immediately drawn to the round keep tower. Hubert was a military man, and his excursions would have exposed him to castles within France at the time. The round keep was developed by Philip II, king of France, against whom Hubert battled. A visit to Villeneuve-sur-Yonne would provide evidence of Philip’s keep. Hubert gained his knowledge and ideas of building them from his visits to France. An example of the round keep a little closer to home is at Pembroke castle where Hubert’s ally William Marshal (who also fought against Philip) built one.

Grosmont Castle

The last of the Three Castles is situated overlooking the village of Grosmont. Park on the high street of the village and walk up a lane where, at its end, you pass through a farm gate to behold Grosmont Castle. Entry is made through a picturesque gate with the name Grosmont forged in and over a bridge. Walking across the bridge shows the steep ditch that was part of the castle’s defences.

Grosmont castle seems smaller than the other two castles visited. There is also a major difference in design here as a distinct hall like structure forms part of the outer perimeter. Attached to two corners are curtain walls that enclose the inner ward. Three towers and the gatehouse are situated in these walls. The walls and towers were constructed by Hubert de Burgh during his ownership. Access can be made to parts of the wall’s walkway and the southwest tower, which is a very pleasant surprise.

The construction that took place in the 14th century is evidenced firstly by the tall octagonal chimney which formed part of the north block. Secondly there are enlargements made to the southwest tower. These would have been completed by the Earl of Lancaster at the time.

Three Castles conclusions

This concludes an unexpected exploration of the Three Castles. It has been a thoroughly enjoyable experience which was greatly enhanced by free admission to all 3!!

The visits brought to life parts of England’s history about which I was blissfully unaware. The tumultuous times of medieval England are fascinating to learn about. King John I (Robin Hood memories and buried in Worcester Cathedral), Henry III (visit to Westminster Abbey), Edward I (warfare against the Scots) were all monarchs of whom I had tiny bits of knowledge, but that has been greatly enhanced during this discovery.

Another aspect of knowledge that has greatly been enhanced is castle architecture. Motte and bailey, palisade, curtain walls, gatehouses, inner and outer wards have all been learned about on this trip. Further inspiration to visit Pembroke Castle is a must along with other marchland castles. A visit to Usk castle also seems to be essential in understanding the local history (watch this space).

So, I leave this delightful area on the border of Wales and England with a spring in my step – the Three Castles has been very educational. I look forward to exploring more of this historic local area.

My latest

My latest

blue bells awash the ground like an artist’s pallet. Add to this the grass and weeds that can’t be touched so as not to ruin the spring flowers. Having read the signs and notices I didn’t jump in to get my picture, unlike the kid on a school visit. The walk along the tree path is a tunnel of green as the trees take full bloom now spring is in full swing.

blue bells awash the ground like an artist’s pallet. Add to this the grass and weeds that can’t be touched so as not to ruin the spring flowers. Having read the signs and notices I didn’t jump in to get my picture, unlike the kid on a school visit. The walk along the tree path is a tunnel of green as the trees take full bloom now spring is in full swing. This is my second blog on my use of

This is my second blog on my use of  person by that name whose wallpapers feature in many a National Trust property; indeed one can visit his house somewhere down Kent way) started

person by that name whose wallpapers feature in many a National Trust property; indeed one can visit his house somewhere down Kent way) started