This blog commences a change in writing style, which I hope you approve. The emphasis up until now has been on facts that have been discovered/learnt on each visit. While this part of the format is retained the visit to Tintern Abbey has highlighted a new area of knowledge.

It is not so much dates against events but the ability of the site to stir the emotions. Coupled with this is the discovery (I am not that well-read) of another era in man’s history. I learned about the renaissance in Italy and Florence and its connection and influence upon the art that I saw there. Of course, the renaissance was not confined to Italy. It became a way of life throughout Europe and almost governed the thinking of the day.

At Tintern Abbey I found out that visits made to the Wye Valley in the late 18th century was the start of British tourism. This led to famous people like Wordsworth and JMW Turner visiting and expressing their thoughts and feelings about the place in either poetry or art. These men, along with others throughout Europe, led the period of man’s history known as romanticism.

This blog will lift the facts about Tintern but also draw on the poetic language, much of which I do not understand, that was used to describe the place. Questions will be asked; it may well be that my language becomes quite flowery. Let’s see…

Iconic Tintern Abbey

Tintern Abbey is a ‘national icon’ situated on the banks of the River Wye in Monmouthshire. It was once a Gothic masterpiece. At the time of the dissolution of the monasteries nearly 500 years ago, the abbey was destroyed, and it became a set of ruins. 200 years ago, however, dare I put it this way, romance filled the air.

Artists and poets alike composed masterpieces of the iconic Tintern abbey. Read on as I explore the site, understand its history and admire the architecture of the abbey whilst learning about the ‘beautiful, ‘picturesque’ (was this a new word in the English language back then) and the ‘sublime’.

Tintern Abbey Location

Tintern Abbey is perched on the western banks of the river Wye. Its location was first chosen for its detachment and remoteness which aligned with the strict behaviour expected of Cistercian monks.

The river Wye meanders its way through the valley and is the 4th largest river in Britain. It runs from its source in Mid-Wales, and acts as the border between England and Wales for about 45 miles before it meets the River Severn.

Tintern Abbey’s prosperity grew under the marcher lords at the nearby towns like Monmouth to the North (11miles), Chepstow to the south (7miles), Usk to the west (15miles) and Raglan northwest (14miles).

Tintern Abbey Architecture

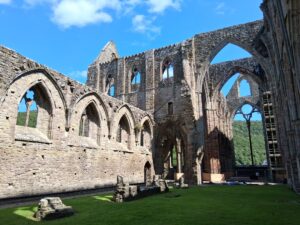

The traditional cruciform plan of the church is evident. The impressive nave, transepts and presbytery are clearly seen from differing angles although not all accessible.

Entrance to the site is made through the main kiosk which leads out to the monks’ living quarters which are to the north of the abbey. There are ruins of the day room, warming house, refectory, kitchen and parlour. Most of all that remains of these is at foundation level. A lot of imagination is needed to visualise its former glories!!

Between these buildings and the northern side of the nave was the cloister.

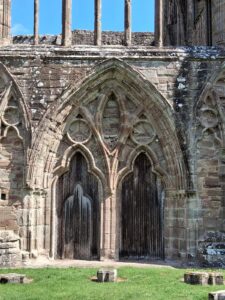

Entry into the abbey itself is through the western end of the nave. The towering gable end shows its sheer size, and particularly, of its nave. The central nave had additional northern and southern aisles at a much lower height than the central nave. The western window towers above the doors and leads to a smaller window above.

The nave consisted of 6 bays. To the northern side remains much of the external northern aisle wall but not much of the northern nave wall. On the south side the pillars and Gothic arches remain with windows above them which are part of the nave wall. The roof over the southern aisle seems to have been repaired and replaced.

The crossing towers straight up and is connected to the nave, transepts and presbytery. Sadly, this is all that can be seen from afar as metal barriers and scaffolding restrict access and views. There is no sign of any of the graves that might have been in the chapel. I am informed that these would have been destroyed during the suppression of the abbey. The tall and elegant windows remain in each of the outer ends of the transepts and presbytery.

Cistercian Order

This was founded in France in 1098 and born out of frustration at the lack of monastic observance in the Benedictine monastic community. The name ‘Cistercian’ comes from Citeaux (Latin, Cistercium) which was the mother abbey in Burgundy, France. The Cistercian Order follows a stricter observance of the rule of St Benedict. It is commonly associated with the wearing of white.

The Cistercian order is part of the Roman Catholic church that flourished in England in the medieval ages. The first Cistercian abbey established in Britain was in 1128 at Waverley (Surrey) with the second to be established here in Tintern. The founding of Rievaulx Abbey in Yorkshire marked the beginning of the development of the Cistercian religious movement in Britain. To delve deeper into the Cistercian order a trip to Yorkshire might prove to be necessary. The county was the heart of the Cistercian community in Britain with several abbeys close by.

The Cistercian monasteries fell from grace and favour when Henry VIII left the Roman Catholic church. The pope did not grant him a divorce and this led to the dissolution of monasteries. This in turn boosted the monarchy’s coffers.

Without realizing, I have already visited a Cistercian abbey and written about it when I first embarked on this learning journey many years ago (Forde Abbey in Dorset). I may have to revisit and stump up the money to visit the inside this time though.

Tintern Abbey History

Founding of Tintern Abbey

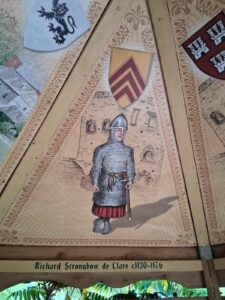

Tintern Abbey was founded in 1131 by Walter de Clare. The powerful ‘de Clare’ family name was discovered on a recent trip to Usk Castle. I’m not sure of the links between Walter (Chepstow) and Richard (Usk) de Clare. The early founding of the abbey consisted mainly of timber buildings, the same as the early motte and bailey castles would have been.

Kingswood Abbey

By 1139 the community was thriving, and the overcrowded Tintern was able to colonize a first daughter house in Kingswood in Gloucester. Roger de Berkeley, Baron of Berkeley and owner of Berkeley Castle acquired the land in Gloucester. Barely anything remains of the abbey in Kingswood save for an Abbey Gatehouse. This abbey is part of English Heritage is free to visit if ever you’re passing by.

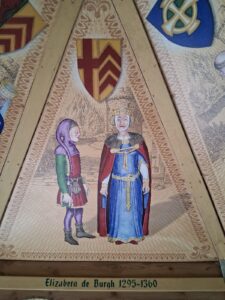

Tintern Parva

In 1189 William Marshal (discovered at Usk castle) became Lord of Chepstow, through his marriage to Isabel de Clare (Isabel and her two sons are buried at Tintern Abbey) and became a patron of Tintern Abbey. William authorized the second and final daughter house of Tintern Abbey on his lands in Ireland and called it Tintern Parva (little Tintern). He had made a promise to God during a stormy sea trip to Ireland that if he remained safe, he would establish an abbey. Ruins remain here and look worthy of a visit if I can make it back to Ireland. The abbey ruins in Wexford Ireland are part of Heritage Ireland.

Roger Bigod III

In 1245 the Lordship of Chepstow passed to the Bigod family. Roger Bigod III took a keen interest in Tintern Abbey. Roger became the Duke of Norfolk in 1270 and continued until 1306. At the turn of the 14th century he granted the abbey a valuable asset, his Norfolk manor of Acle. Roger is the man who helped to build the church we admire today. Works began in 1269 and were completed in 1301. Such was his impact on the abbey that when the dissolution of the monasteries came the monks were still distributing alms to the poor 5 times a year in repose for Roger’s soul.

Royal Visitor to Tintern Abbey

Tintern Abbey had a royal visitor in 1326 when Edward II took refuge at the house when fleeing Roger Mortimer’s army. He spent two days at Tintern Abbey.

William Herbert

In 1469 William Herbert (1st Earl of Pembroke, known as Black William) was beheaded after the battle of Edgecote and buried at Tintern. The Herbert family was discovered in detail at St Mary’s Priory, Abergavenny (his father and mother are buried there, along with his brother who was beheaded with him).

Dissolution of the Monasteries

The destruction of the monasteries began in Henry VIII’s reign. As previously learned, this was done in two acts, the first in 1536 and the second in 1539. The monasteries owned about a quarter of the land in England.

Henry acquired a lot of wealth by removing them. Tintern Abbey fell peacefully in the first Act of Supremacy. The abbeys in northern England revolted which led to the ‘Pilgrimage of Grace’ in October 1536. In this first act small monasteries and abbeys with an income of less than £200 were closed and their buildings, lands, and money taken by the crown.

The larger abbeys and monasteries fell in the second act of suppression in 1539. Tintern Abbey was sold to Henry Somerset, the then current Earl of Worcester. Henry would go on to strip the monastery of its valuable resources. Tintern Abbey, like many other abbeys, fell into ruin.

Romantic Tintern Abbey

Tintern Abbey’s fate was to take a turn for the better in the 18th century. A popular engraving in 1732 by the Busk brothers started it all off. Reverend William Gilpin’s best-selling account of ‘Wye River Voyage in 1770’ described Tintern as ‘the most beautiful’ scene of all and people were hooked. Whether or not his description was accurate is a matter for debate (there is a comments box at the bottom of this blog – I would love to hear your thoughts on all matters raised in this blog as well as all others).

Gilpin was a notable travel writer, an artist, a church of England cleric and a schoolmaster. He is famous for being one of the first promoters of the term ‘picturesque’. William also wrote ‘Observations on the River Wye’, which was first published in 1782. He evidently felt that the River Wye was the place to visit.

It could be argued that the early Romantics were revolutionary but the observation of events in France (the Reign of Terror) resulted in a shift towards the power of nature and the importance of the imagination. The French Revolution and Napoleonic War kept travelers out of Europe and adventurers wanted to explore the wild landscapes of Britain. The ivy-covered ruins of Tintern were to provide inspiration for poets searching for the ‘sublime’ and ‘picturesque’. This brought a flock of people to the area and as a result, British tourism commenced. The guidebook had come to stay!!

JMW Turner painting of Tintern Abbey in 1794

J.M.W Turner was a romantic landscape painter. Renowned for his oils, he became one of the greatest masters of British watercolour landscape painting. His work is now in galleries all over the world. The painting relating to Tintern is now housed in the Tate Modern in London and I must see it for myself. The painting in question shows the crossing of the abbey looking towards the East Window. He beautifully captures the elegant glamorous ruins of Tintern Abbey complete with its ivy.

William Wordsworth's famous poem (1798)

William was an English romantic poet. Along with Samuel Taylor Coleridge (he was born in Ottery St Mary in Devon, and I must go to see the superb church there and the graveyard for its Coleridge connections) they launched the Romantic Age in English literature. They wrote a book together called ‘Lyrical Ballads’ which a collection of their poems. William included his poem associated with Tintern. William revisited Tintern Abbey 5 years after his first visit and famously composed ‘Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey’. He describes the gentle sounds of the rivers and streams running down the ‘steep and lofty cliffs’.

Tintern Abbey conclusions

There was once a seductive allure to these mystical ruins. It was once a place of seclusion, detached from life and home to those who followed a strict devotion. Those monastic times seem a long time ago. They were a long time back and were ended abruptly. The church which provided a sanctuary was left to become a heap of ruins.

As if by poetic justice, the Romantic era, coupled with the input of a devotee to the Wye valley itself, gave the ruins a new meaning and a new beginning. People were stirred to visit these towering and overgrown ruins. The ivy crawling around pillars of stone with the sun or moonlight beaming through vacant arches, open windows and a roofless building as captured by the artist became inspiring.

My reaction on Tintern Abbey

Sadly, these romantic ruins that provided so much inspiration didn’t and don’t have the same allure for me. Yes, they’re incredible to witness. It is nice to see its roofless splendour and the towering size of a once monastic masterpiece. Imagination is also needed above ground level. Ugly scaffolding sticks to the building like a forgotten plaster. The rest of the site is a sterile theatre, a doldrum of corporate preservation and presentation.

The noisy sounds of cars passing by drown out those gentle sounds of rivers and streams, though, to be fair, Wordsworth wouldn’t have been troubled by motor cars. To be fair to myself, Wordsworth hardly described the abbey but the river by which it is located. The poem seems to eulogise the power of nature to restore and has nothing to say about something man-made like the abbey.

He seems to delight in nature itself, and one wonders whether he could have been having the same thoughts as he did in another place with his dancing daffodils. To me the people at the turn of the 18th to 19th centuries led much less sophisticated lives than modern man and, evidently, were inspired.

Perhaps the current works will enhance the site – they will do nothing to curb the engine noise.

Listen to me going all Wordsworth and yet describing the antithesis of the romance of the place. Am I being too controversial? Does Tintern Abbey deserve this level of controversy?

I’m intrigued to know your opinions. If you have been please let me know your thoughts. Were you romantically inspired? In a fast-changing world did you feel the urge to get your easel out? Or jot down a few words of poetry. Do you find the place pleasing on the eye?

If you haven’t been, have I inspired you to go? Has Gilpin, Turner or Wordsworth? Leave your thoughts in the comments below….