Tuckers Hall is an historic building in Exeter. Almost camouflaged from view, Tuckers Hall is nestled on Fore Street and is a supposed ‘must do’ of Exeter. After visiting I would concur. It is not, however, the place you would naturally stumble across or perhaps even notice.

It was during some pre-trip planning that I found out about this lesser-known site. Described as ‘a remarkable survival’ and originally built as a chapel, it is a testament of Britain’s enduring history. Join me as I delve into the history and explore the lesser-known Tuckers Hall.

Visiting Tuckers Hall

Tuckers Hall Location

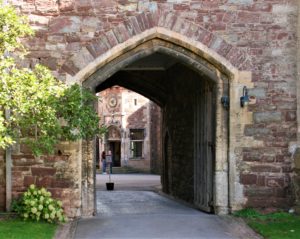

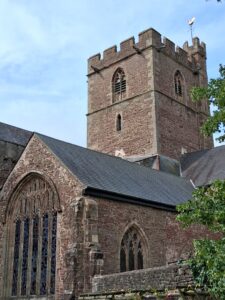

The historic Tuckers Hall is sandwiched between the local and independent shops of Fore Street in Exeter. Fore Street is a road that runs downhill from the city centre towards the river Exe. At the start of Fore Street is St Olave’s Church. This fascinating church is worth visiting and sits opposite the Exeter corn exchange. Halfway down Fore Street you will see an alleyway pointing to St Nicholas Priory (Exeter’s oldest building), just after that is Tuckers Hall.

Tuckers Hall Opening times

To visit the Tuckers Hall careful planning is required. The site is only open for visitors on Thursdays and Saturdays between 1030 and 1300 all year round. From the beginning of June through to the end of September Tuckers Hall also opens on a Tuesday (1030 – 1300).

Contacting the Hall prior to visiting is advisable and potentially may open opportunities to visit outside these hours. This is of course at the Hall’s discretion. All other times the site is generally closed. The hall can be hired for private events and functions.

Admission prices to Tuckers Hall

It is free to visit Tuckers. Bonus! Donations are of course welcome. Maintenance of an historic building is not cheap. I donated £5 and couldn’t believe it that in return I was given a guidebook and postcards. The guide was invaluable in providing knowledge of this fantastic building.

Tuckers Hall History

Beginnings

Tuckers Hall began life as a chapel. In 1471 the guilds of clothmakers known as the Weavers and Tuckers (will learn more about these later in the post) were given a plot of land by William and Cecilia Bowden to build a chapel. This was a place that they would be able to meet and worship. The building/chapel was known as the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

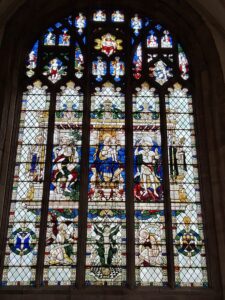

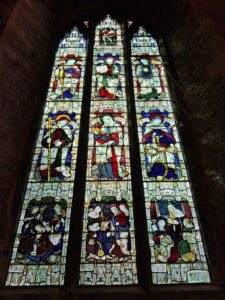

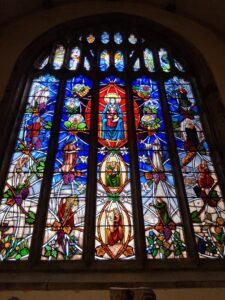

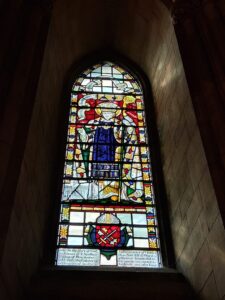

The walls were constructed out of local red stone with a spectacular timber wagon roof. Entry was gained through the entrance that is still used today. There were 6 perpendicular windows installed, only one remains to this day.

In 1490 Shearmen were added to the title of the guilds. As it became common practice to group certain trades together. In 1564 the guild received its Grant of Arms.

Reformation

I would never have guessed that the origins of this building were religious. That is due in part to the fact that religious aspect of the hall was removed during the massive upheaval of the Reformation. To save it passing to the crown it was sold to a member of the guild.

After the Reformation major structural changes were made to the building. A complete first floor was installed which separated the building into two distinctive areas and resembles the current layout of the place. The lower floor was turned into a school room and the upper floor into a Court room. A chimney was also added around this time along with changes to the windows, the wagon roof was covered in plaster and murals were painted on the walls.

Royal Charter

In 1620 King James granted the guilds the status of ‘Incorporation of Weavers, Fullers and Shearmen’. This was the result of ‘jack of the trades and master of none’ types infiltrating the system and giving Exeter and the region a bad name. Not only was the reputational damage severe, so too was the impact on the prices of goods exported.

The Royal Charter gave the guilds the ability to set the standards of producing quality not quantity of cloth. This also gave them an independence to govern themselves, control production, maintain standards and conduct their business without interference by the city officials.

The Golden Age

With the king’s seal of approval, sorry I mean, Royal Charter, Exeter flourished, and the excellence of their product propelled the city into the golden days. It became the 3rd most important city outside of London.

After the turbulent times of the English Civil War the impact of the golden age was fully felt as developments within the city such as a provincial bank was built (first outside of London), and a navy was created to protect and export their product. I’m sure a visit to the Exeter quay will be enlightening.

In 1634 oak panelling was installed to hide the wall paintings just prior to when the Civil War broke out. The Civil War was negotiated, with the city loyal to the Royal cause. Further research may prove if the charter brought loyalty from members of the guild to the crown.

In Exeter’s golden age there was an increase in production to a staggering 1,000 pieces of cloth being produced a day. That resulted in around 400 master craftsmen belonging to the guild. Exeter’s importance as the 3rd city in England was confirmed by producing about 25% of the country’s woollen cloth. 70% of Exeter’s population was employed or in associated trades with the Cloth industry.

Revolution

The industrial revolution and wars of the time brought an end to Exeter’s cloth trade. By the year 1850 the trade was over. The building would fall into a poor state. The guild was finding a new way to survive. One member managed to save the building from demolition when they paid for the front wall to be rebuilt.

Modernisation

Early in the 20th century the building was given a new lease of life. Major works were completed in 1908 to expose the roof timbers. A new entrance corridor and traditional staircase were also installed. Electricity arrived at the site in 1936.

Yet the ‘site’ and the ‘Incorporation’ weren’t sustainable. The trade on which it was based was a thing of the past. It was decided to expand the membership to include local businessmen and tradespeople.

Educational Tuckers Hall

The knowledge learned has been picked up from two valuable sources of information. Firstly, the guidebook that I acquired when I donated. Secondly, from the valuable information signs dotted around the site.

Weavers

Weaving is a process that refers to the production of the cloth. Weavers in the title refers to the master weavers of Exeter. Across the county of Devon this role was done by children, men and women. In the Guild, work was completed by ‘Master Weavers’. The masters employed apprentices who would do most of the work as they took a back seat.

The weaving process has some main terms associated with it, loom, warp, weft and shuttle. I will not try to explain each one as I don’t fully understand it myself, but I will quote my guidebook.

“Weavers used a loom, a wooden frame, on to which yarn known as the ‘warp’ was secured from top to bottom. Then other yarns were woven in and out through the warp from one side of the frame to the other using a tool called a ‘shuttle’. These second lengths of yarn were known as the ‘weft’.”

Tuckers

The name given to the persons responsible for cleansing and thickening of the cloth. The woven cloth still contained the sheep’s natural oils and greases. This cleaning process was done by pounding and kneading the cloth in water which turned it into the finished article.

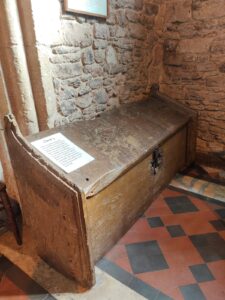

The first step in this process was the scouring. Cloth was covered in soda and soap before being put through troughs of hot water. It was then put through rollers or stamped on. In the second stage the wools were taken to Exeter’s water-powered mills. The clothes were put through the ‘fulling stocks’ (a model of which is shown on the ground floor of Tuckers Hall). This is where the process of large wooden mallets pounded the cloth. The cloth was then finished with a final wash.

Shearman

In the upper hall, on the middle table appeared to be ‘larger than normal’ scissors. They were in fact a pair of shears. The final stage of the cloth business required a strong and steady hand. The cloths were laid out on tables so the “shearing” could be completed. This highly skilled task was well paid and would take several hours as perfection was sought and a reputation was built.

Beadle

Another name picked up from my visit to the hall was that of ‘The Beadle’. According to the dictionary a ‘beadle’ is a ceremonial officer of church, college or similar institution. This is confirmed after reading one of the information signs dotted around the building.

The Beadle’s role is an important one in the day-to-day running of Tuckers Hall. Evidence of this was confirmed on the visit as it was the current Beadle who showed us around whilst answering numerous phone calls and directing staff and deliveries.

The Beadle’s duties also cover leading the Master and Wardens in civic processions, welcoming visitors and ensuring the security of the building. The Beadle also holds a key part in the Incorporation’s dinners and functions, where they take on the role of master of the ceremonies as well as ensuring the necessary gowns and regalia are there for the Master.

Tuckers Hall Architecture

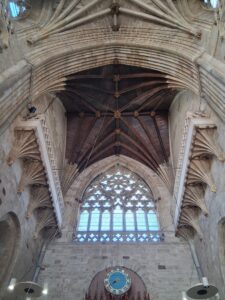

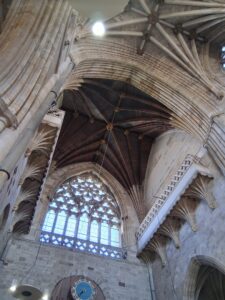

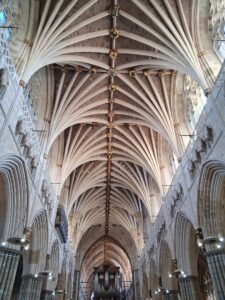

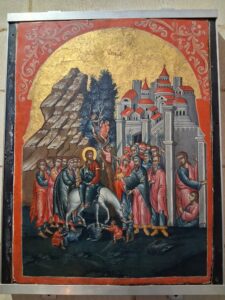

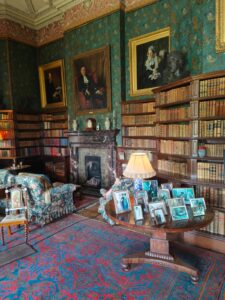

The architectural brilliance in this building is on full display when you walk into the upper hall. The wooden wagon roof is fine example of carpentry. Bosses seem to take shape on the ceiling, I assume these are bosses as they look like those seen at Exeter cathedral.

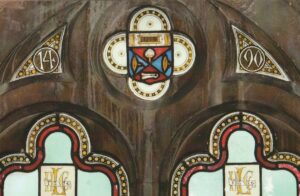

On the south side of the building light pours through the plain stained-glass windows. Closer inspection shows one of the windows top pieces displaying the ‘Grant of Arms’ which is made up of the key tools used by the guild.

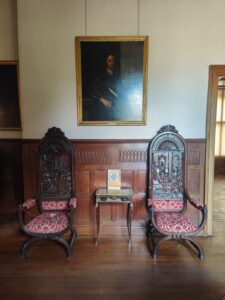

On the walls is the oak panelling. These hide any evidence of the murals painted on the walls. The oak panels are fascinating to look at; 11 grotesque masks have been carved into panels at differing points. Heraldic shields also adorn the panelling. In the mantel piece tools of the weavers and tuckers trade are also carved in.

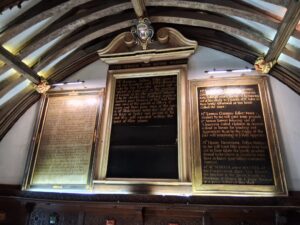

At each end of the room are two other notable pieces. One is the royal coat of arms which I would guess is associated with the royal charter. At the opposite end are three tablets. The tablets record the charitable endowments of notable members of the guild.

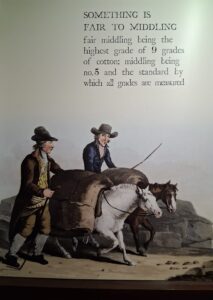

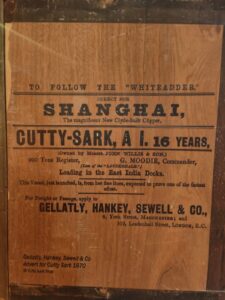

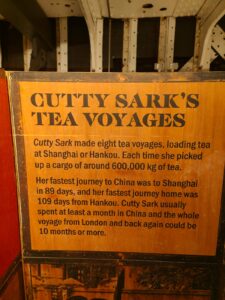

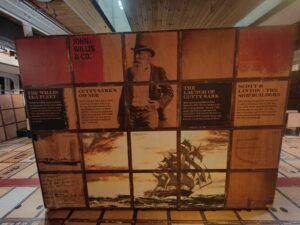

Tuckers Hall Phrases

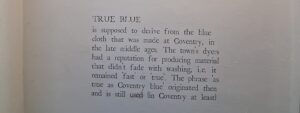

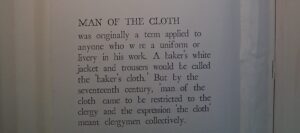

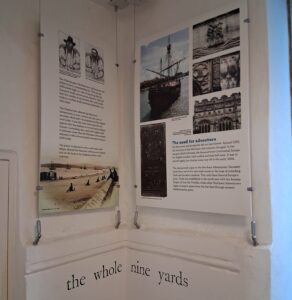

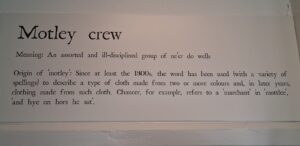

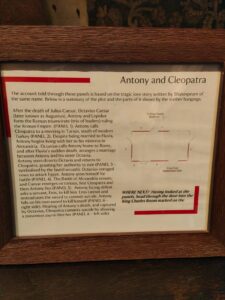

I will leave below pictures of phrases that were displayed around the building relating to cloth trade. They certainly caught the attention.

Tuckers Hall Summary

Tuckers Hall is a little gem in the city of Exeter, a secret perhaps few know about. The building is a ‘remarkable survival’ with the upper floor an intriguing delight to witness. The building is a joy to discover; the wagon timber roof is wonderful. On the ground floor are display boards making a fascinating learning experience which caters for all.

As I leave there is an optimism in the air that I have discovered one of the cities hidden gems. I’m sure there are more to find, not only in Exeter but in all towns and cities that I visit. I would be fascinated to know of any ‘lesser known’ places you may know about that I should discover for myself. I will continue to keep meandering my way around the country, exploring and challenging myself to find those gems and bring them to your inbox.

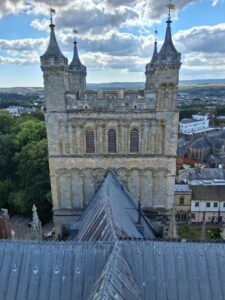

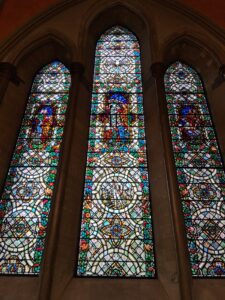

Now, I am not averse to entering a church, abbey or cathedral. I find them good places to calm down and contemplate life. Often, I am there alone with my thoughts but on this occasion (as was the case in July 2022 at St Paul’s cathedral) I was there with my father. He, like me, was bowled over by the fact that a timed entrance slot had to be pre-booked and further surprised to see so many people inside

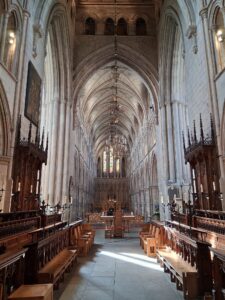

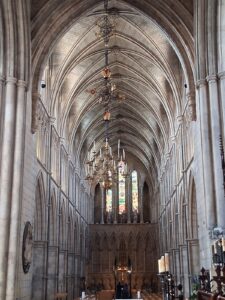

Now, I am not averse to entering a church, abbey or cathedral. I find them good places to calm down and contemplate life. Often, I am there alone with my thoughts but on this occasion (as was the case in July 2022 at St Paul’s cathedral) I was there with my father. He, like me, was bowled over by the fact that a timed entrance slot had to be pre-booked and further surprised to see so many people inside  The building is very famous, strikingly beautiful and massively interesting. To me it was an intriguing and beguiling place. To us Brits there seems to be a lack of appreciation or willingness to visit such iconic places but to foreign tourists, there appears to be incredible levels of fascination. The ‘abbey’ is situated in the heart of central London, in the city of Westminster (some people refer to Westminster as one of its boroughs, however, I call it one of London’s two cities) and a short walk from the River Thames. It stands

The building is very famous, strikingly beautiful and massively interesting. To me it was an intriguing and beguiling place. To us Brits there seems to be a lack of appreciation or willingness to visit such iconic places but to foreign tourists, there appears to be incredible levels of fascination. The ‘abbey’ is situated in the heart of central London, in the city of Westminster (some people refer to Westminster as one of its boroughs, however, I call it one of London’s two cities) and a short walk from the River Thames. It stands Church, Abbey or Cathedral?

Church, Abbey or Cathedral? Royal Peculiar

Royal Peculiar Mausoleum?

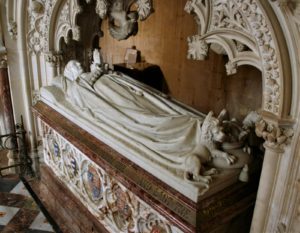

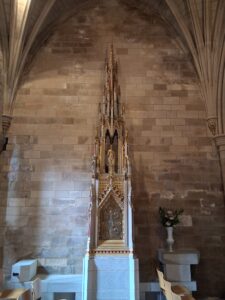

Mausoleum? Henry VII Lady Chapel

Henry VII Lady Chapel Coronation Church

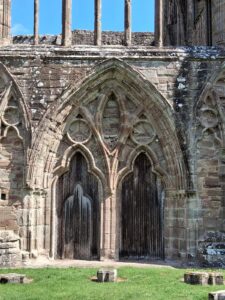

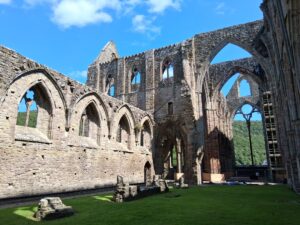

Coronation Church Gothic Masterpiece

Gothic Masterpiece