In the heart of Florence and at the eastern end of the Piazza Santa Croce, stands the impressive Basilica of Santa Croce. A tall, elegant and grand church which on first impressions immediately appeals to my inquisitive mind. The church was built on former marsh lands that were outside the old city walls in what was often referred to as the poor part of the city. Santa Croce is the largest Franciscan church in the world.

In this visit I discover about the Saint Francis Assisi, the man who gave up his family’s fortune to pursue a life of God through poverty. He became the patron Saint of Italy and founder of the Franciscan church. The Franciscan order is characterized by total poverty. Its links to its past and origins might seem strange when exploring the church. Plain on first sight, an intimate walk around proves that this church is a treasure trove of wealth and art. Join me as I discover why this church is often referred to as the Temple of Italian Glories.

History of Santa Croce

Santa Croce’s history begins with the spreading of the religious message of Francis of Assisi. He was a spiritual leader who set out to follow the example of Jesus Christ by following the gospel accounts after giving up a life in the military. He devoted his life to serving God and helping the poorest in society. His following, referred to as Franciscans, arrived in the winter of 1209 to build a church and monastery in the poorest part of Florence.

As times changed, wealth and money started to pour into the city of Florence. Wealthy merchants donated their newfound money to the building of a new church. As Florence became a powerhouse of the Middle Ages the church was rebuilt before being enriched and modified. Fires and floods added complications and resulted in more modifications and improvements to the church and the complex.

By the 19th century Santa Croce had established itself as a ‘must visit’ tourist site. People from all over Europe would come to visit the church. But at the time of the Napoleonic suppressions the Franciscans had to give up the church and monastery which was taken over by the military with barracks set up in an area of the complex. By the time Napolean was defeated Santa Croce was given back to Franciscans in 1814.

Shortly after the wars came the unification of Italy, a subject I must confess to knowing little about. The ‘House of Savoy’ and the ‘papacy’ are all subjects to learn about as my exploration of this country continues. Before Rome became the capital of Italy, the honor fell to Florence. It was during this period that the church became the property of the central state.

In the year 1933 Santa Croce was elevated to the honorific rank of Basilica. The floods of 1966 almost destroyed the church, but the church survived and has been the subject of intense restoration ever since.

Santa Croce Façade

Standing in the middle of the Santa Croce square the impressive façade stands tall and proud in front of you. The façade that is seen today was financed in part by an English Protestant magnate, Sir Francis Joseph Sloane. Sir Francis had made his fortune from a local Tuscan copper mine. When I have some more time I will explore if there is a link between Sir Francis and a namesake square in London.

The façade is the work of architect Niccolo Matas who finished the façade between 1853 and 1865. It is clad in white marble and framed in green marble, a very traditional Florentine appearance from the Middle Ages and Renaissance. This is an appearance that is all too common in the rest of the city. In my eagerness to enter the church I really didn’t pay much attention to the details of the façade. At the top of the façade, surprisingly is a star of David. Rumors are this was built here because Niccolo was Jewish.

Monument to Dante

As I leave the square and make my way around to the entrance of the church, I cannot miss the tall and imposing monument placed near the church. On closer inspection I find out this is a monument to ‘Dante’.

I must confess to knowing nothing of the man and must add this to the list of research and self-education after my visit. A quick search teaches me that he was a famous Italian poet, philosopher and writer whose famous work was ‘The Divine Comedy’. The first section of this work includes what is known as Dante’s Inferno and is a medieval description of hell. The monument seen here today is from 1968, but the original statue dates to 1865, the year of grand celebrations of the famous Dante’s birth in 1265.

The creation of this monument was planned to coincide with the completion of the new façade. Its original location was in the middle of the square before it was moved to its present position. When it was unveiled in its new location the new king of Italy (Victor Emanuel II) was there for the unveiling. According to my guidebook, the base is adorned with two Marzocco, the heraldic lions of the old Florentine republic.

The basilica of Santa Croce

The construction of the current church was started in 1294 to replace the old church founded by St Francis and his followers. Santa Croce translated means ‘Holy Cross’. The design of the church was by Arnolfo di Cambio.

In recent visits I started to comment on how churches are constructed in the shape of a cross. Santa Croce is no different, except that its floorplan is in the form of a Tau cross. I was blissfully unaware that there were different types of crosses. A Tau cross is a T shaped cross and is called a Tau because it is shaped like the Greek letter Tau which in its upper-case form has the same appearance as the Latin letter T.

Entry is made on the north side and into the nave and not through the western entrance in the ornate Façade. Towering arches have been built on octagonal pillars on either side of the nave. Looking upwards to the ceiling, a very bland set of timber trusses contrast beautifully with the white arches.

The nave itself simmers. All is silent as visitors walk slowly round, appreciating all that is before them. The feeling I had was this was a church that is yet to be discovered by most tourists. This leaves time and space to learn and appreciate one of Florence’s less visited sites. As I walk round to the western entrance to start my visit properly, the high altar at the far end of the nave seems spectacular and worthy of a detailed look. There is so much to see that not all can be seen in the one visit. I’ll be back.

Temple of the Italian Glories

Interspersed around the chapels of the basilica Santa Croce, on both floors and walls in both the nave and aisles are several tombs, graves and elaborate monuments to notable Italians. As my exploration of Florence, Tuscany and Italy broadens I’m sure a better education will take place on some of the names I’m about to mention. This place is known as the temple of Italian glories (we in England might use the word worthies). It is a who’s who of Italian history. Santa Croce went from an initial graveyard, which served the Franciscan friars before wealth and power dictated more elaborate monumental tombs and graves to be placed within its walls. As a result, Santa Croce became the guardian of Florence’s glories.

It started in the 15th century with two tombs for Leonardo Bruni and Carlo Marsuppini, two literary figures who earned their fame as chancellors of the Florence Republic. The signoria (local government) stumped the costs of these graves which began the transition to Guardian of Florence Glories. Cosimo de Medici revived the tradition of using the church to honour the great and good when he commissioned the monument to world renowned sculptor and artist Michelangelo (famous for his painting in the Sistine chapel and his David sculpture). Others would take a leaf out of his book as monuments were added, most notably for astronomer Galileo, and political philosopher Machiavelli (from whom we get our English word Machiavellian).

From the 19th century onwards, the church transformed from Guardian of Florence’s glories to the Pantheon of the Italians. A monument to Vittorio Alfieri was completed in 1810 before a cenotaph of Dante Alighieri was erected in 1829 (he is still buried in Ravenna). Monuments and tombs to Gioachino Rossini (who was buried in Paris, before his body was removed and brought here) were added at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1871 the remains of Foscolo were also transferred to Santa Croce. Efforts were also made to try and bring back Dante’s remains but, sadly, agreement could not be reached.

There are over 250 graves and monuments to explore and about which to learn. I won’t bore you with the details of each one but challenge you to see it all for yourself if visiting Florence – you won’t be disappointed.

The Masterpieces

Santa Croce’s origins as a Franciscan Church seem almost forgotten when viewing the incredible artwork that adorns the place. This church is so rich in its fabulous works of art that it almost defies the Franciscan order of poverty. There are around 4,000 pieces of work, ranging from the 13th to 20th century which bless this church and complex. One can only imagine the arts of work here are priceless as most of what is seen is original.

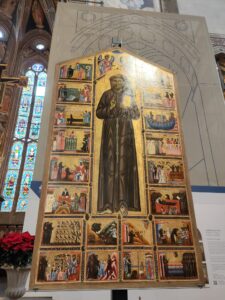

Some of the highlights include the main altar, surrounded in frescoes of the ‘Legend of the True Cross’ by Agnolo Gaddi. The frescoes by Giotto. There is the Cimabue crucifix dated 1288. There is the Bardi altarpiece. 3 pieces of work by Donatello, the crucifix in painted wood, Saint Louis of Toulouse in gilded bronze and the Annunciation of the Virgin. Construction of Pazzi chapel by Brunelleschi. Michelangelo’s tomb, Salviati’s ‘Deposition’, Bronzino’s ‘Descent’. The list could go on and on.

The 16 chapels built within the church, combined with the greater church complex, draw inspiration for so many and even influence some. In the 19th century French author Stendhal visited Florence and Santa Croce, and he was overcome with emotion. He wrote “I was in a sort of ecstasy, from the idea of being in Florence, close to the great men whose tombs I had seen”. Stendhal syndrome was born, also known as Florence syndrome which occurs when individuals are exposed to such magnificent art.

In Conclusion

Santa Croce was a great place to start my education on the beautiful city of Florence. The basilica of Santa Croce certainly wasn’t on my list of places to be visited constructed prior to arriving. There are reputedly more famous and iconic attractions in the city. So, I’m grateful for the recommendation to visit by a dear friend.

What was learnt at the basilica has built on knowledge gleaned in recent meanderings. I had learnt how that a church’s floorplan represents a cross, but these meanderings further enhanced that knowledge base as I learned that there are different types of crosses. The basilica is a combination of the grandiose Gothic architecture, the tombs of great Italians, the perfection of Brunelleschi’s Pazzi Chapel and some of the finest examples of Florentine painting.

Its origins date back to one of the two patron saints of Italy, Saint Francis. This has given rise to an interest in visiting Assisi (Umbria region, south of Tuscany in central Italy) if the opportunity arises. I found out that some of the great people of Florentine and Italian history are buried here. Not only did the basilica provide the perfect place to start exploring but also has inspired me to visit and explore Ravenna (where Dante is buried).

So, I leave the Basilica of Santa Croce behind and meander off in search of the next jewel in Florence’s crown.